‘The Story of Janakye Bai’ by Vithai Zaraunker, brings to fore a long-preserved Velip folktale from Goa

RAMANDEEP KAUR | NT KURIOCITY

Assistant professor in the Women’s Studies Programme at D.D. Kosambi School of Social Sciences and Behavioural Studies, Goa University, Vithai Zaraunker studies oral traditions, indigenous knowledge, community stories, gender and social issues. As a member of the Velip community, her experiences of discrimination in school and college influenced her academic path. During her postgraduate studies, she learned how dominant ideas often label some communities as “backward” or “primitive”. Today, she works to preserve and honour the knowledge in her community’s stories, songs and memories.

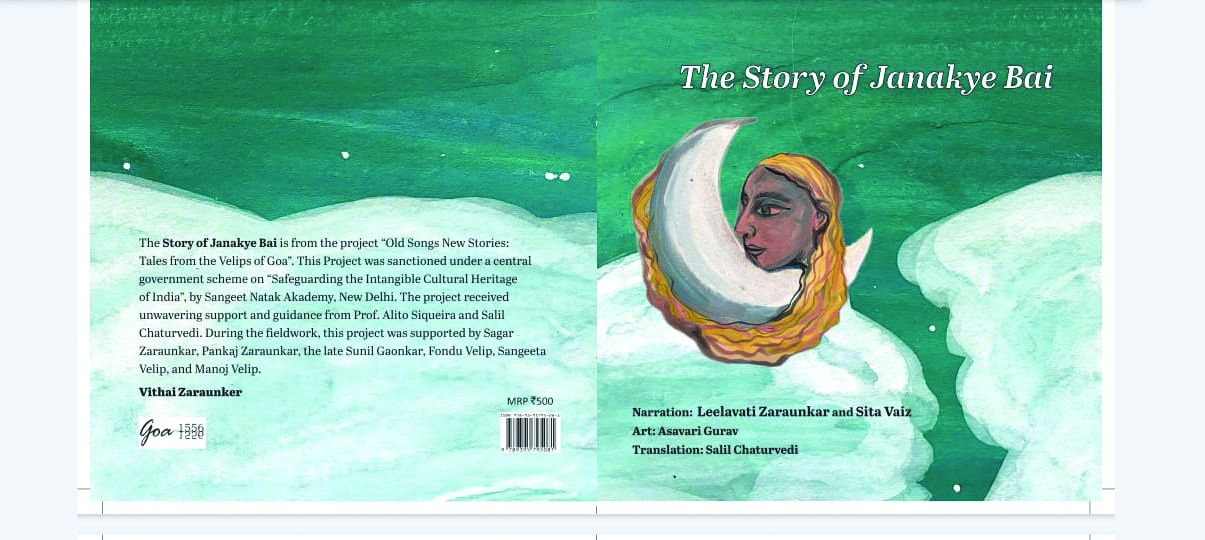

Her first book, ‘The Story of Janakye Bai’ is a centuries-old folktale from Goa’s Velip community, narrated by traditional storytellers Leelavati Zaraunker and Sita Vaiz. It tells the story of a young woman who resists a forced marriage and also shows Velip values, wisdom, and connections to nature and the spiritual world. Illustrated by Asavari Gurav, the book preserves a story passed down orally for generations. The work has been translated and edited by Salil Chaturvedi with guidance from Vithai Zaraunker.

Published by Goa 1556, the book grew from Vithai’s project ‘Old Songs, New Stories: Tales from the Velips of Goa’, started during her master’s studies at Goa University. The project was supported by Sangeet Natak Akademi and JSPS KAKENHI and guided by the late professor Alito Siqueira.

Excerpts from an interview:

Tell us a little more about the book

‘The Story of Janakye Bai’ is a retelling of an important Velip folktale. It includes the full oral narrative, verses, and songs linked to the story, illustrations capturing the spirit of the tale and QR codes that lead to audio recordings so readers can hear how oral tradition sounds. The book functions both as a storybook and as documentation of living oral heritage, preserved largely by women of the community.

How did the ‘Old Songs, New Stories’ project lead to this publication?

The ‘Old Songs, New Stories’ project allowed me to travel to Velip villages, meet storytellers and singers and record oral narratives. Through these interactions, I realised how rich our culture is and how little of it exists in written form. The idea of documentation grew from this process and the book is one outcome of a long journey from fieldwork and recording to shaping the material into written text.

Why was it important for this work to be led from within the Velip community rather than by outside researchers?

My community seeks justice from historical and epistemic marginalisation. Stories are not just data; they are memory, dignity, and identity. Indigenous communities are often represented by outsiders who romanticise us or portray us as backward, primitive or without knowledge, focusing only on surface aspects of culture. Our knowledge systems and the exploitation we face rarely appear in academic work. Only someone from within can truly understand the stigma and discrimination faced by the community and ensure the stories are told accurately.

Since the story changes with every telling, how did you decide what finally went into the written text?

The story itself does not change but the sequence or characters may shift depending on mood, memory, audience and context. There is no single correct version; what matters is the meaning within the story. The written text is one recorded version based on narrations by both storytellers. I also included audio recordings to honour its living, changing nature.

What were the main challenges of translating a living oral tradition into a book?

Many words in the story are difficult to translate because they do not exist in ‘standard’ Konkani. There was also the ethical challenge of representing community voices without appropriating them.

How did the guidance of the late professor Alito Siqueira contribute to this project?

Professor Siqueira encouraged me to value oral knowledge as serious scholarship and helped me believe that my story matters. His guidance gave me the confidence to move from silence to documentation and taught me to view research as an act of healing and reclamation.

How did your collaboration with storytellers Leelavati Zaraunker and Sita Vaiz come about?

The collaboration began during the ‘Old Songs, New Stories’ project. Leelavati Zaraunker is my mother. I have also known Sita Vaiz since childhood. Our relationship is based on trust, kinship, and shared identity. They are the true carriers of Janakye Bai’s story; I only helped it move from voice to page.

What does the story of Janakye Bai reveal about the moral values and worldview of the Velip community?

The story shows values of courage, resistance, choice and consent, along with connections to nature and the spiritual world. It shows how moral codes and wisdom are transmitted through storytelling and challenges the idea that tribal women are silent. Janakye Bai is a symbol of strength and independence.

How does this book challenge the way tribal and marginalised communities are usually represented in academic and public spaces?

The book challenges portrayals of tribal communities as backward or merely objects of study. Instead, it presents them as knowledge producers, storytellers and ethical communities.

What do you hope young people, especially from the Velip community, will take away from this book?

I hope they feel proud, value elders and oral traditions, speak their language freely, and see that their culture is not inferior. I want them to become future storytellers, researchers, and writers, and understand that they define themselves, not others.

How will the next books build on this work?

The upcoming series will record more stories, songs, and women’s narratives, preserve the community’s language and memories, and challenge stereotypes. By moving from a single story to many voices, the series will continue to be led from within the community and strengthen indigenous scholarship.

“My community seeks justice from historical and epistemic marginalisation. Stories are not just data; they are memory, dignity, and identity. Indigenous communities are often represented by outsiders who romanticise us or portray us as backward, primitive or without knowledge, focusing only on surface aspects of culture. Our knowledge systems and the exploitation we face rarely appear in academic work. Only someone from within can truly understand the stigma and discrimination faced by the community and ensure the stories are told accurately.”