TENSING RODRIGUES

Last time we said, Geniza records have ample evidence of the trade through the Valipattan port; but the trail goes dry on the ground. We have nothing to show; no structures, no objects, no inscriptions. However, all is not lost. Ample patience and hard work have shone light on a new form of evidence. Let us pursue it now.

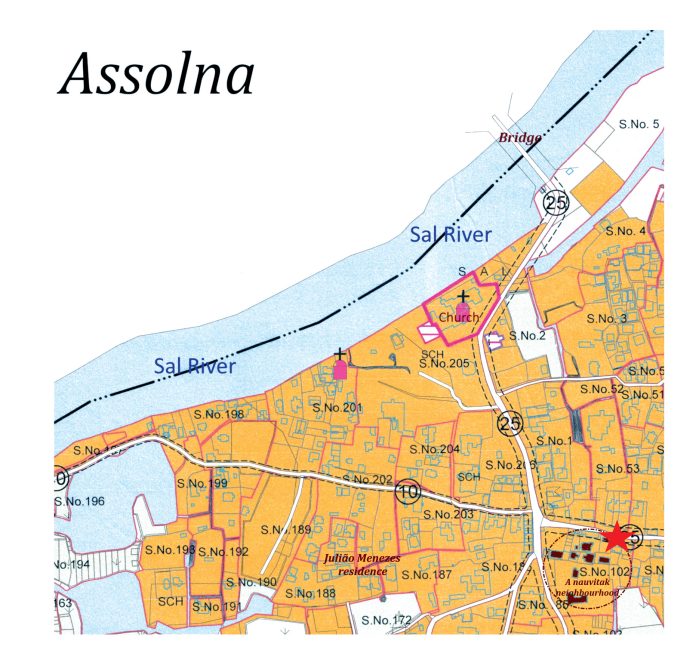

It’s for this pursuit that we go to Assolna. But before we get on the ground, we need to do some digging into history. It is a rather long history; but a captivating human story that the visitors to the site will definitely love to listen to. It begins more or less in a couple of thousands of years after the end of the last Ice Age (Ice Age ended about 10,000 years ago). We cannot go so much back in time; we begin a 1,000 or 2,000 years ago.

Nevertheless, it will take us much time to reconstruct the history from the scattered jigsaw pieces; but we must; because it is a story that hardly finds mention in the history books. And in Assolna you have living evidence of that

history.

It is about a time when the Kathiyavad (Kathiawar) peninsula, the hump in the Gujarat map between the gulfs of Kaccha (Cutch) and Khambhat (Cambay) accommodated a long garland of ports, spread in both the gulfs and in the Nal-Bhal depression connecting them. That was the hub of trade between the west coast of India and the Middle East (think of Aden), connecting further to Europe through the Mediterranean (think of Venice). But at the end of the last Ice Age when the sea level rose, Kathiyavad was submerged. A good part of it has now become the Rann of Kutch – a large salt marsh. After the submergence, the traders fled in search of alternative sites for ports. These traders were essentially ksatriya from the eastern Indo-Gangetic plain, with a genetic infusion of Kirat (Chinese) who had come into Indian Peninsulavia Arunachal Pradesh around 6,000 BCE. Earlier, the Kirat were in trade with Middle East and Europe by the trans-Himalayan land route, and were now looking for a shorter and easier route. This genetic mixture (eastern ksatriya + kirat) we have called ‘kathiyavadi ksatriya’, for want of a better name. The kathiyavadi ksatriya traders sailed down the west coast in search of alternative ports. They seem to have found some ports on the Goa and Tulunadu coast. In Goa, we have called them kathiyavadi caddi (chadd’ddi) (in Goa, ksatriya are called ‘caddi’). In Tulunadu, the kathiyavadi caddi are called ‘bunts’. They have distinguishing physical features revealing their mixture of ancestries. They are usually tall and fair with light eyes. As a bunt puts it in his blog “I am a bunt originally from Udupi and the paddanas (paddanas are narrative legends describing the story of many Tulu spirits, their origin and heroic deeds and prowess.) described us as the ‘nagavansham’ kshatriya, the original ‘nag-aradhakas’ (serpent worshippers) who came from the serpent kingdom of Ahikshetra in the north. … Akshikshetra is somewhere in Uttarakhand near Nepal-Tibet border. Also, many of us bunts, at least I, have slight mongoloid features not very prominent; but you can observe many of us bunts, not all, have slightly smaller eyes like B. R. Shetty or Ajit Shetty of Jannsen Pharmaceuticals or even Aishwarya Rai, whose eyes are slightly smaller and curved. This again points to Scythian Naga origins. … Some of us bunts are tanned but never dark.” [Mundkur & Vishwanatha, 2010: Bunt and Nadava Evolution – An Outline, in Tulu Research – A Blog, https://tulu-research. blogspot.com/2010/01/222-nadava-evolution-outline.html] Among the kathiyavadi caddi in Goa too, we find these distinguishing physical features revealing their mixture of ancestries. But they are not always pronounced. In some generations they are prominent enough to be easily discernible; in other generations they are latent. But, be they kathiyavadi caddi of Goa or bunts of Tulunadu, trade is their passion.

In Assolna, we find several neighborhoods of kathiyavadi caddi. Now, how did they land in Assolna? Most probably these are the families of ‘nauvittaks’ or ‘nakhudas’ who operated in Valipattan. “Among the diverse types of merchants active in India during the first half of second millennium, the ship-owning merchants occupy a prominent position in the coastal areas of Western India. These merchants are given distinct epithets nakhuda and nauvittaka, the two terms being occasionally used as interchangeable,” writes Chakravarti. “These ship-owning merchants can be considered as elites in the ports of coastal Western India.”[Chakravarti, 2,000: ‘Nakhudas and Nauvittakas:Ship-Owning Merchants In the West Coast Of India’, in The Journal of The Economic and Social History of the Orient, 34] Both the terms correspond roughly to ‘big ship owning merchants’. They probably owned ships and carried on trade as well. Geniza Documents abound in examples of such persons even in Goa. Chakravarti, for instance writes about a “nauvittaka Aliya who was followed by his son Muhammad and grandson Sadhano at Gove”. [Chakravarti, 1999: ‘Candrapur/Sindabur and Gopakapattana: Two Ports on the West Coast Of India AD 1000 -1300,’ in Proceedings of Indian History Congress, 153.] Gove refers to Old Goa; but most likely Aliya was based at the Mandovi tributary at Kalapur coming from the Bambolim/Cujira hills.

We have no way to say why these nauvittak settled in Assolna rather than Velim; may be because Assolna was more inland, and they preferred to be away from the hustle and bustle of a port; which they often did even elsewhere.

One finds such families in Chandor (Chandrapur port) as well; the Menezes Bragança, Cunha, and Fernandes families are prominent examples. The two ports – Valipattan and Chandrapur – were most likely contemporary. But we do not know why, the kathiyavadi caddi families around Valipattan seem to have lost their sheen. Their grand mansions with high plinths and private altars still stand; but many of them find it difficult to maintain them and their own lifestyle. I give below a short excerpt from what appeared in O Heraldo of June 19, 2020:“A diminutive man in his mid-sixties put 17 coconuts in his bag plucked from his tree and stood in the balcão at the entrance of his family mansion, waiting to catch a ride with this reporter back to Margao. His name: Zeferino Ravi Menezes. His mission: to sell his coconuts to a few restaurants.” The write-up was about Zeferino Ravi Menezes, the nephew of Dr. Julião Menezes, perhaps the best known among the kathiyavadi caddi of Assolna. Julião was the man who brought Ram Manohar Lohia to Goa; Menezes and Lohia had studied together medicine and economics at Berlin University. This is just one example of kathiyavadi caddi families around Valipattan who have lost their sheen; there are many more whose mansions are crumbling and grand private altars are covered to prevent further decay. However, some have succeeded in reviving their fortunes.

This tourism project could help them to regain their lost glory. If that happens, it will be a win-win situation: not only will Goa get to showcase a lost glorious chapter of its history; but the project will generate resources to conserve the lost treasure. If the project generates income for the residents of these neighbourhoods, they will be maintained better. And the stakeholders in the tourism project will also find it more viable. Though it has been implemented in a haphazard manner, I see the Latin Quarters project in Panaji blooming. Managed better, it could have been very successful: properly showcased and well planned, the Latin Quarters could have delivered better returns to the businesses there, and created less nuisance for the residents of the locality. The place has tremendous tourism potential given its proximity to the Rua de Ourem creek. One needs to see the business paradise built by Malacca around such a creek, showcasing the Chinese Malay neighbourhood.

Let us visit Latin Quarters some other day.